UX of Text

BRIEF: Design an encounter that values patience, presence, or pause

Group members: Jaime Santos, Revati Banerji, Xiaoqin Qin, Vibhooti Sharma, and Sakshi Pansare

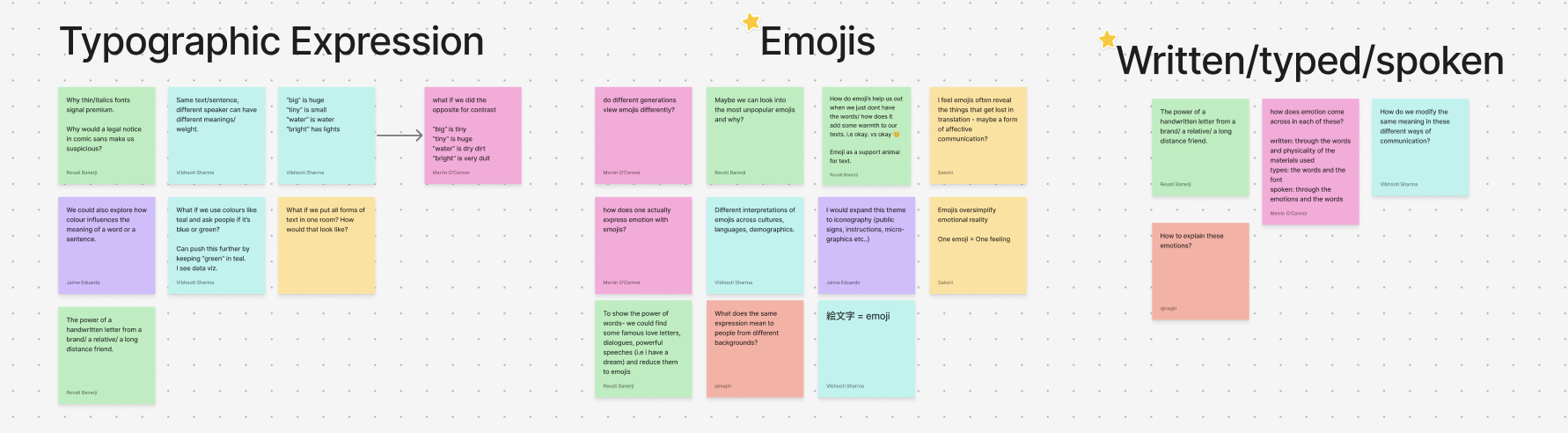

After this brief was presented to us, I started to notice that our lives and safety depend on text. Whether it’s telling us where to go on the Tube or when to stop, text is a fundamental tool in our society. We started this week by affinity diagramming, which we later learned that we went about all wrong. First, we wrote down topics that interested us and then made subtopics outline where we neededto collect data. Finally, we then grouped all the observations to find common themes.

Our initial affinity diagram, shown above, is more of a mind-mapping technique.

We then decided to focus on the relationship between text and London pubs. We went into our data collection stage, considering what Hayles (2002) writes in Writing Machines,

“We must learn to see text not as an immaterial conduit but as a material object that shapes meaning. ”

When we went to the pubs for research, we applied the understanding that text is a material object and is all around us. A text's quality and placement shape all actions that take place in its vicinity. Many of the pubs we went to shared material qualities with each other, like chalkboards with specials, beer taps, creditcard reader, etc.

Our research led us from Elephant and Castle to Borough Market, and at each stop, we made sure to get photos of every piece of text from the beer taps, the writing on the toilet stalls (O’Connor, 2025).

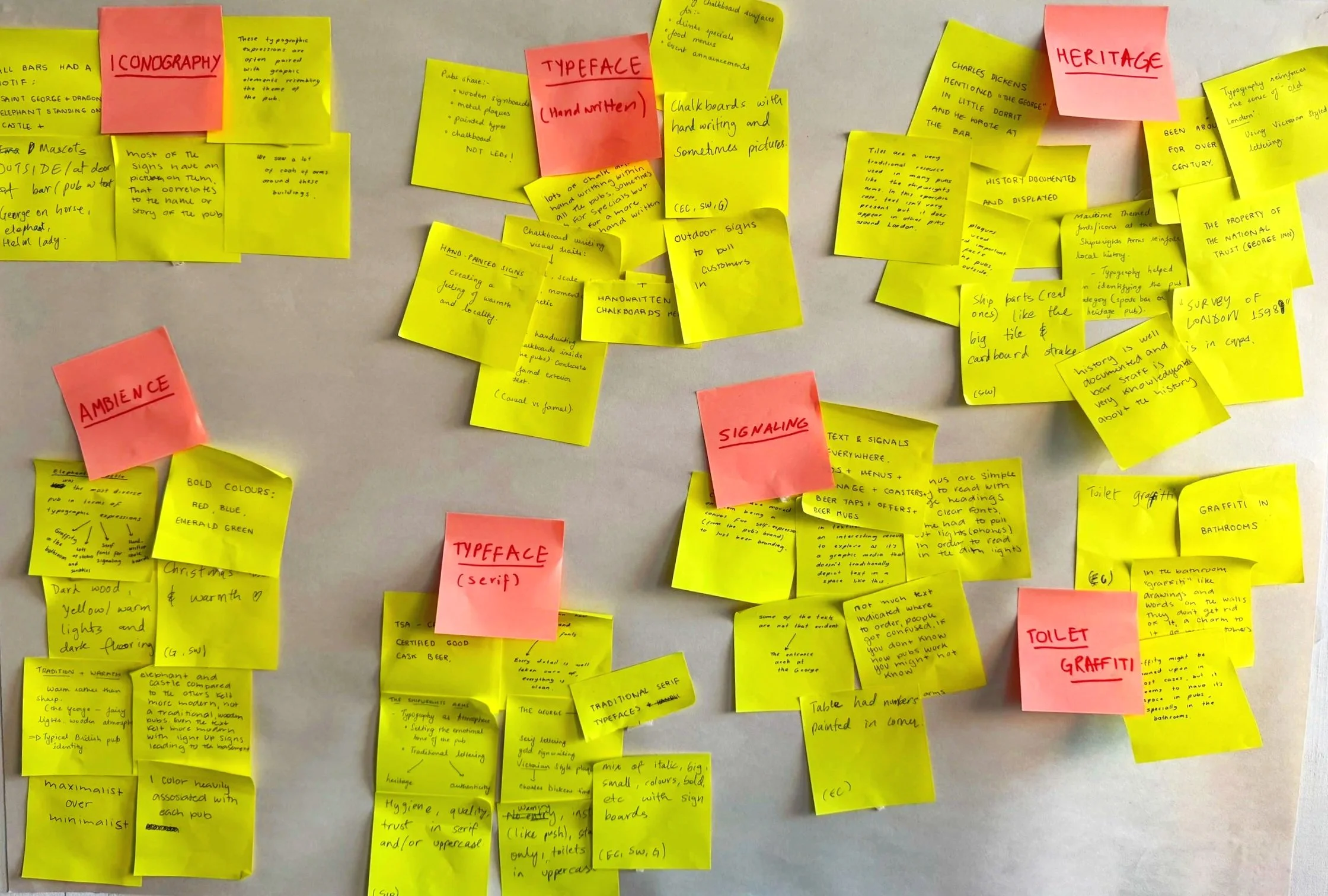

After we observed and photographed these pubs, we had our data set ready for 2nd attempt at the affinity diagramming method. The two that stood out the most were the names of the pubs being tied to the images on the signs, and also the writings of text in the toilets.

The second affinity diagram presented us with 7 themes that ultimately led to a few ideas that we took note of as we continued our research process (O’Connor, 2025).

During our midway presentation, we presented those two themes. Many of our peers and tutors encouraged us to take the less glamorous route and find out more about why people write on the walls of toilets.

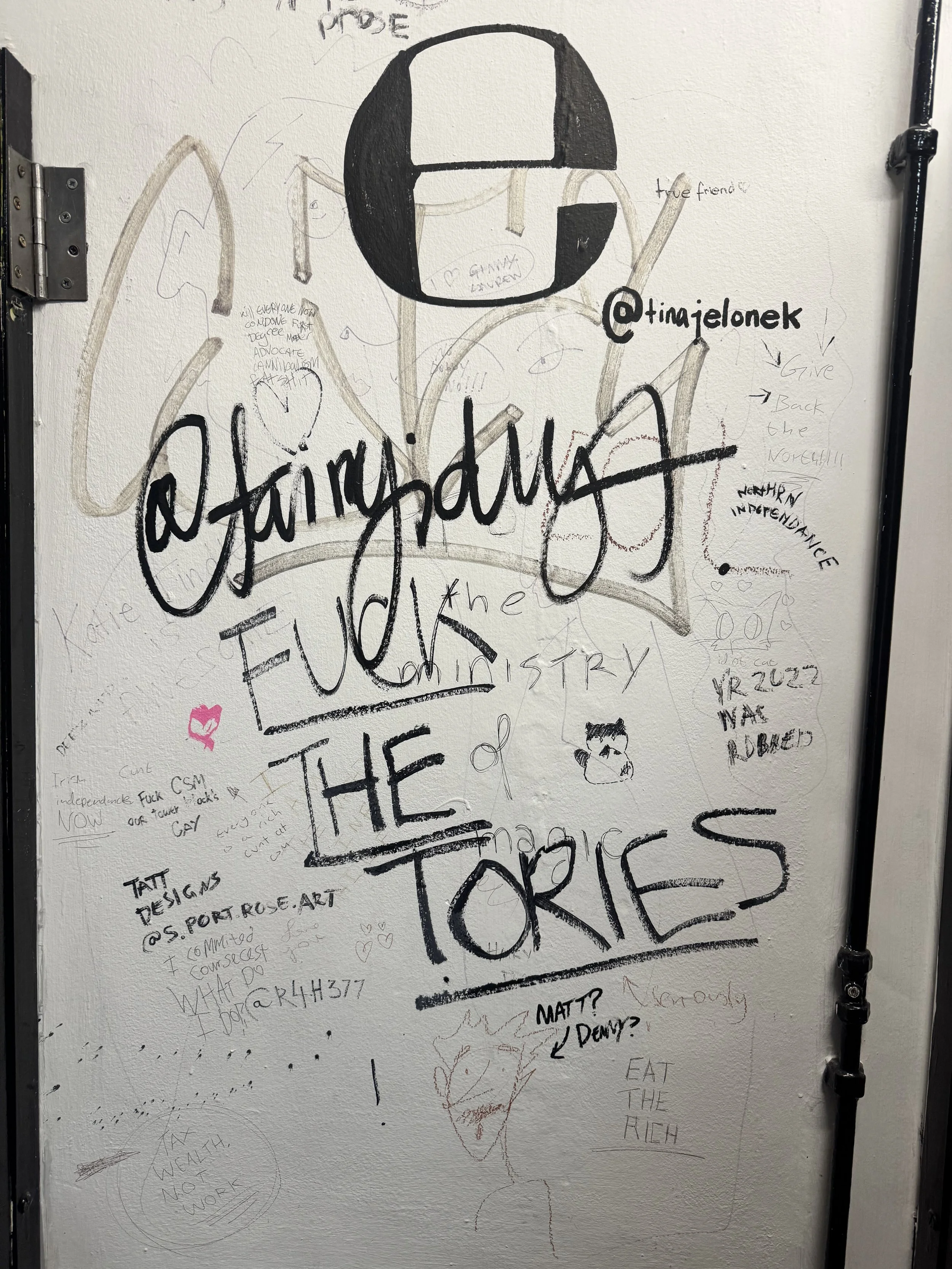

This is when we started more specific research about the toilet graffiti concept. After doing secondary research, I found an interesting journal that showcases restroom wall art as a safe house, specifically in relation to students (Victoria, 2024). Students can share messages and become a part of an environment. We visited our LLC bar, where toilet graffiti acts as decoration and students can anonymously express themselves.

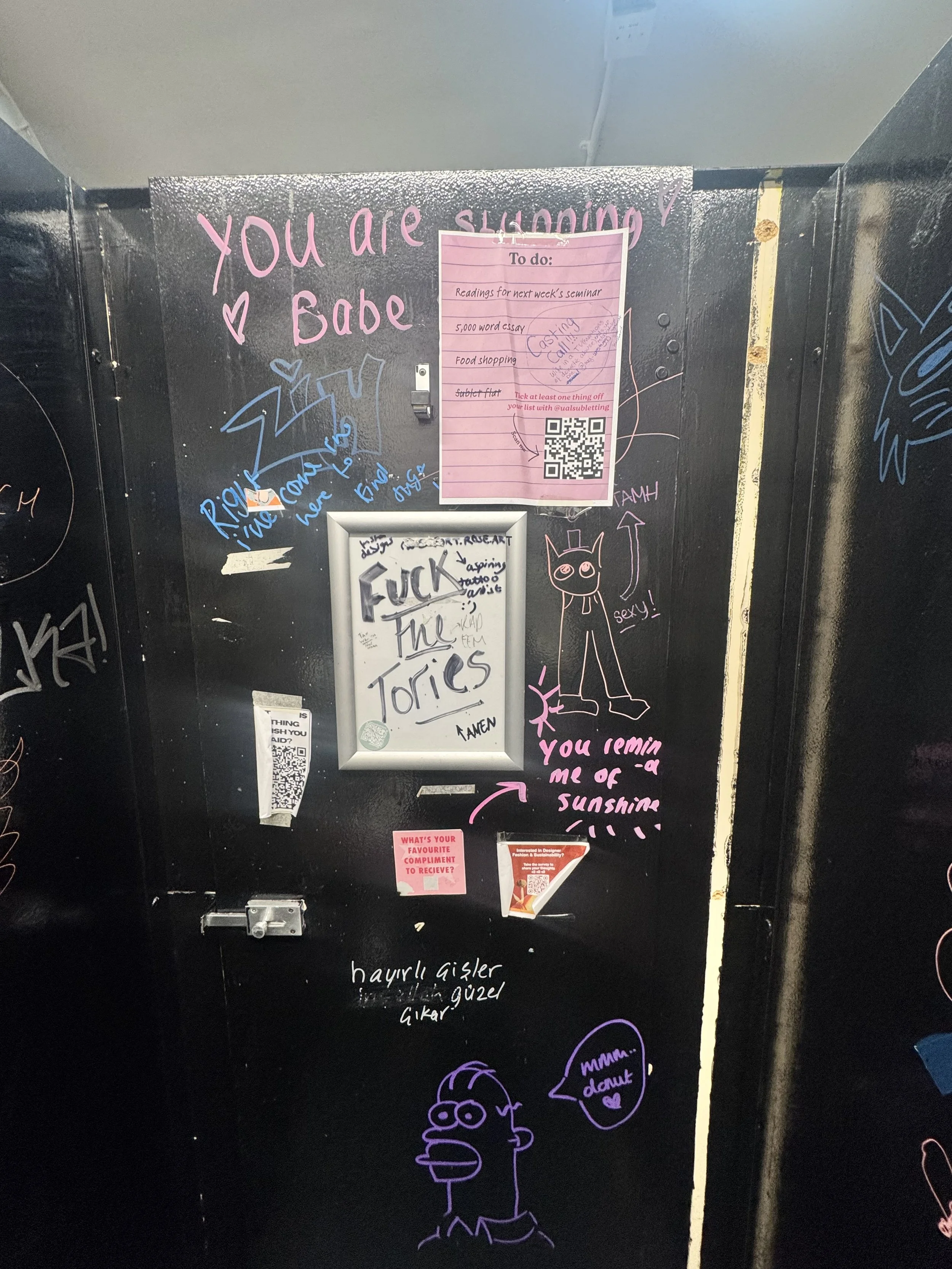

In the Darkroom (LLC Bar) bathroom, we took note of some of the phrases people wrote, looking for a common topic that might help us when it comes to data physicalization (O’Connor, 2025).

The next step was to find more toilets to collect data for our data physicalization, as we need a more specific data set. For our data physicalization, we want to create categories for different types of graffiti on the walls. We then decided to go to Soho to look at more pub toilets.

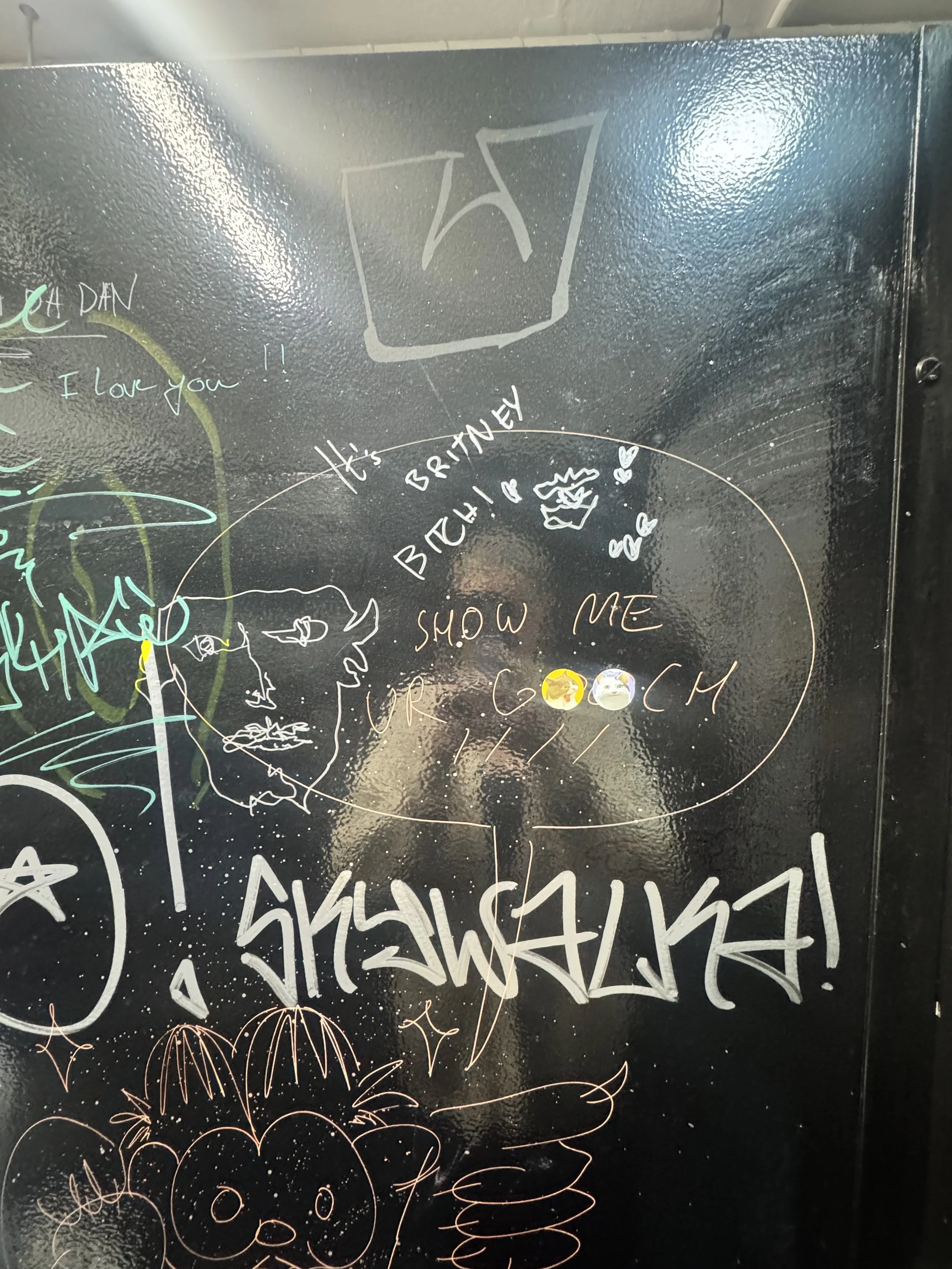

After our research trip to 9 pubs in Soho, we found a term called laternialla, which perfectly described the text we were researching. Laternillas is a bathroom text that consists of informal, mostly anonymous text (Victoria, 2024).

While many of the pubs in Soho did not have extensive amounts of laternilla, we explored some other areas and found places where lanternilla is a part of the over aesthic of the establishment (Santos and Sharma, 2025).

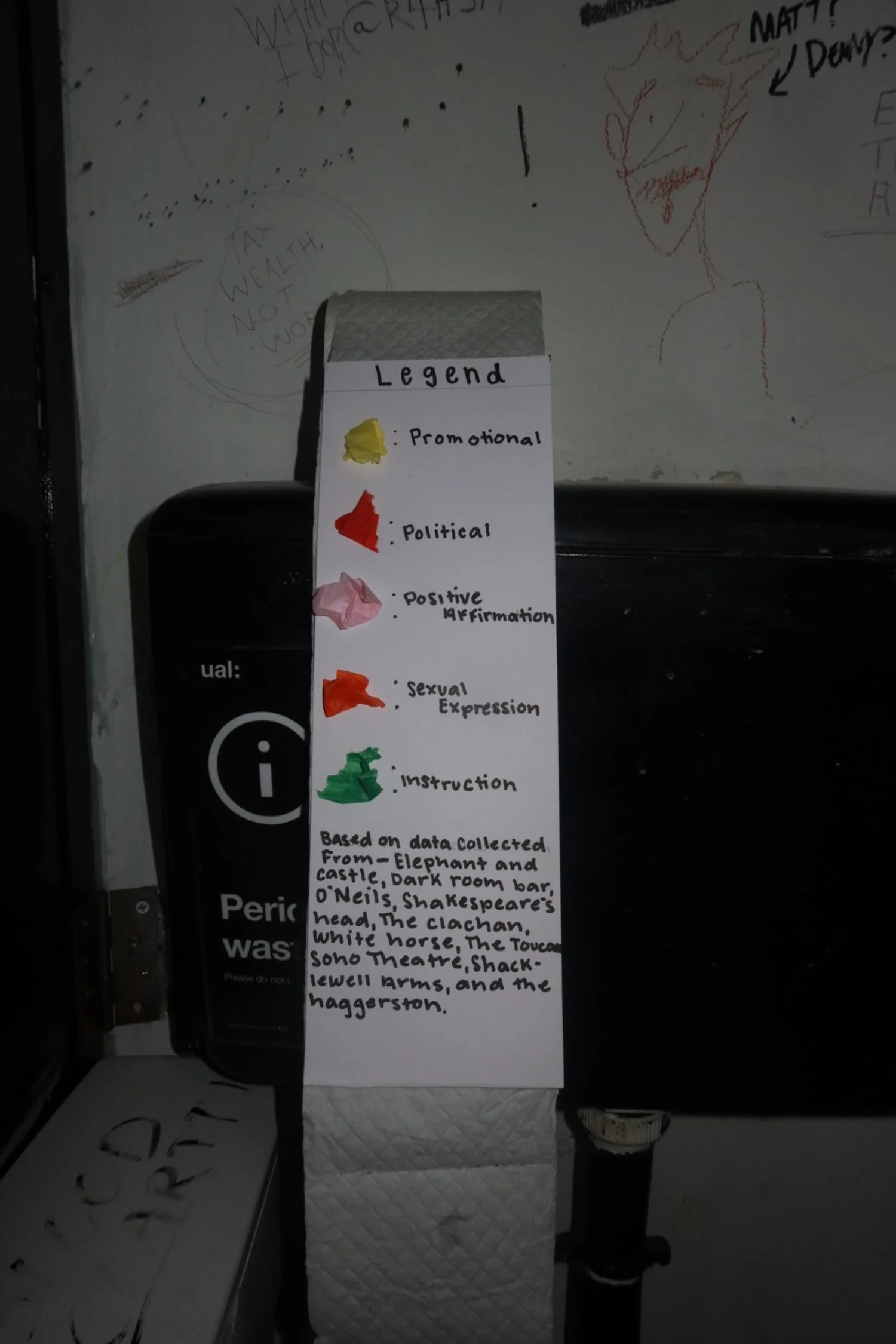

All of these pubs provided us with more insight into what people write and where people write laternialla. This content-specific data helped us group the graffiti into 5 different categories for our Data Physicalization. We wanted our visualization to exist in the same space as we discover the data, so we put our data in the toilet.

Using Saran Wrap and gloves, we placed our data set in the toilet, as it represents what surrounds the toilet. The legend is also attached to a toilet paper roll, adding another sensory aspect (O’Connor, 2025).

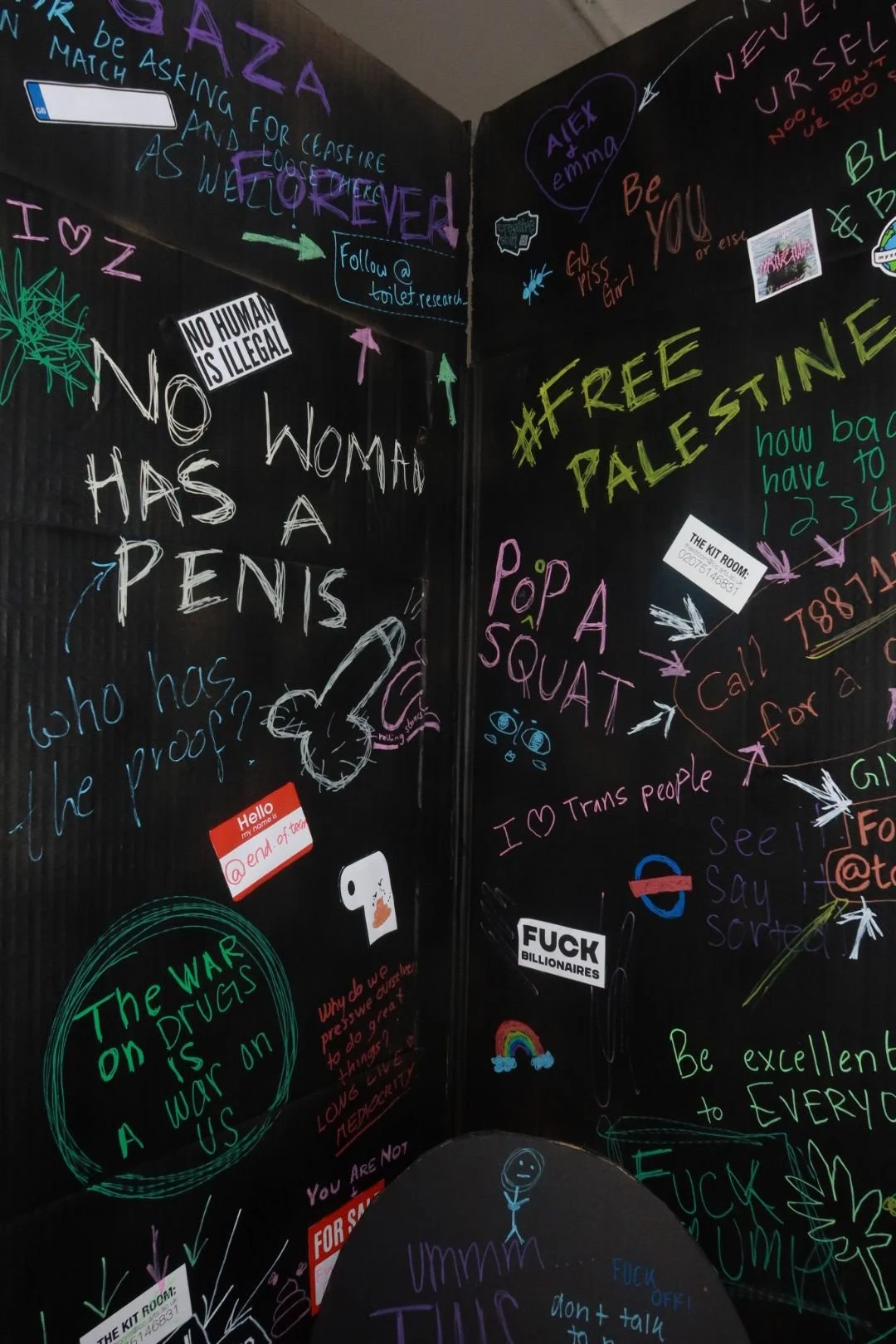

When we completed our research methods, it was time to start creating our idea. We knew that making a full toilet stall was not going to be easy, but we wanted to emulate the privacy that many feel when expressing themselves through laternialla.

There were many stages of our design process, including measuring toilets, spray painting, and experiencing laternialla for ourselves (O’Connor and Sharma, 2025).

Once the stall was built, we prioritized words, images, and stickers that fell into the 5 categories we used in our data physicalization. After we had written our observations, we invited our classmates to come and express themselves in any way they wanted, as we wanted the stall to show more than just the data will initially collected. It was important for us to let people write anything they wanted, and most writings fell into one of our categories.

Time-lapse of our group and our classmates adding graffiti to the final prototype. We needed to add text before the presentation because if there was nothing on it, it would not be anonymous (O’Connor, 2025).

Final photos showcasing a zoomed-in view of the stall (O’Connor, 2025). Group photo in front of the final product (Bangera, 2025).

As a group, we walked away feeling happy with our final product. It was described as a “very designerly project,” which made me feel confident that my skills are developing in the right direction. Our peers said they love that they were given a canvas to express themselves and become the designers of this work in a way. If we took this project further, we would love to leave it somewhere in UAL for all students to anonymously express themselves.

“Dirt is just matter out of place”

Dr. John Fass mentioned this quote, and I plan to refer back to it as I move forward in the course. As we were able to take something gross and make meaning out of it.

References

Frayling, C. (1994). Research in art and design. Royal College of Art Research Papers, 1(1).

N. Katherine Hayles (2002). Writing Machines. The MIT Press eBooks. The MIT Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/7328.001.0001.

Victoria, M. (2024). ‘This Wall Does More for Mental Health than the Uni Does’: Theorising Toilet Graffiti as Safe House for Students. Innovative higher education. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-024-09712-w.